Our systems in education often don't make sense when you boil them down to fundamental reasons for existing. When we recognize this, and acknowledge that change needs to happen, we tend to make the mistake of trying to work within the faulty system. It's not always our fault, because we, as teachers and administrators, do not always have the power to design systems or set policy, but we might be guilty of not making enough noise and arguments against them as regularly as we should. We also tend to avoid trying out systems which might work better, out of fear of ruffling feathers. I see a trend in education -- important and effective change rooted in equity and the meaningful development of young learners always seems to come from K-12 educators. When we let anyone else design the systems they always end up rooted in misguided beliefs and/or greed. So we need to be that change.

When systems are in place that are rooted in nonsense, bias, outdated or obsolete situations, or sometimes, seemingly nothing, change needs to start with deconstruction and building up from a new foundation. The process of deconstruction of education systems has some parallels to the form of literary analysis. You often end up going so deep that you realize that previously held truths are either nonexistent, subjective, or complex and dynamic enough to be impossible to use as a foundation for a static system. Deconstruction is difficult and uncomfortable, but often necessary to build a system based on a solid foundation of moral structure and just motives.

Aliens and the big picture

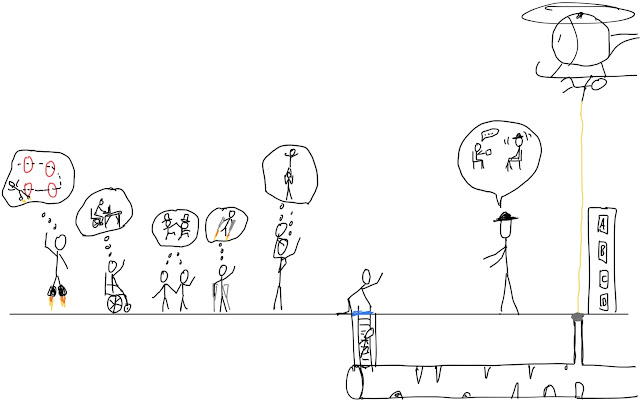

In order to get the best appreciation of how ridiculous a system is it helps to back out for more of a big picture view -- the 30,000 foot view, if you will. This allows one to see how backwards a system might be before diving into the details and trying to deconstruct it. Sometimes this big picture view makes the system crumble and reveals the underlying issues immediately. It's like auto-deconstruction. Big picture TNT. Getting the big picture view is not always easy, especially when you have been working in the system. You are part of the system and the system has become part of what you do. You cannot see the forest for the trees.

To help get the big picture view I like to pretend I am trying to explain a system to a friendly curious alien who is somewhat familiar with our culture and society. Imagine you have that alien sitting down for a cup of coffee and she has a rudimentary idea of how our society functions.

Let's take one of my favorite topics to deconstruct -- grading. Imagine trying to explain the alien what we grade for K-12 students and why. We grade students on compliance and on retention of information. This information can be almost instantly accessed by anyone on the planet. Imagine the alien inquires more about the details of the process, and then we have to start explaining that most of what we base their grades on is stuff we ask them to "learn" but which we know they most likely will never actually use. Not only that, but we use those grades to decide what kind of access students will have to future opportunity. I imagine the alien follows up by asking why you don't grade things that actually matter to development and learning, like the skills they will use.

Let's do another -- school start time. Imagine trying to explain to that alien that while it is well known that adolescents cannot effectively learn early when you make them wake earlier than their biological clocks say they should, and that doing so not only has measurable negative effects on learning but that lack of sleep has been shown to cause permanent brain damage, but that we do it anyway because a handful of extra curricular activities would be inconvenienced. Be ready to explain why learning so much useless information is deemed important enough to harm students. I imagine the alien follows up by asking why you don't just start school when it makes sense and build everything else around that.

How about another? Summers off. Imagine having to explain the the alien that it is well known that giving students a 3+ month break in the summer has measurable negative effects on education but that we do it because . . . we don't actually have a good reason. We just do. There were a handful of bad reasons the trend started a long time ago, but now we just do it because of the tourism industry and tradition. I imagine the alien follow up by asking why you don't just spread out the summer break throughout the school year.

One more. Subjects. Imagine trying to justify why you would separate art, math, writing, language and science into separate subjects with little-to-nothing connecting them. You have to explain that you are a math teacher who teaches only math skills, but you do not work with the other teachers who teach the classes where those math skills might be useful to make sure connections are made with skills and application. Pick a subject and you can most likely find a trend of teaching and learning that is missing many important connections to other subjects. I imagine the alien follows up by asking why you don't just combine subjects to make it all more relevant and connected.

Okay, just one more. Standardization. Imagine explaining to your new alien friend that while you know each individual student is different, with different interest, abilities, passions, skills, and that children grow and develop and different rates, that we decide to hold them all the the same standard at the same time with the same testing methods that don't really test their development and growth. Not only that, but we use those test results to figure out what track they should be on, and in many systems we make it quite difficult for them to get off of those tracks, even when they show great growth. I imagine the alien follows up by asking why we don't just figure out where students are in their development and interests and adjust their education accordingly.

I can keep going all day long on big picture views, but I think that's enough for now. I don't want to spoil any more future blog posts.

Diving in deep, without aliens

What about when the big picture doesn't seem to reveal big problems with a system, but we see evidence that there are problems? The imaginary alien coffee date might not work for auto-deconstruction for every system, or for someone who is closely tied to the system -- can't see the forest for the trees. Sometimes we have to start digging down into details to find reasons that the big picture view might hide.

For example, let's look at AP classes and AP tests. If you try to explain this to an alien the big picture might sound like it makes sense. Kids take these classes that prepare them for these tests which give them credit and a head start at the next level. It allows the more motivated and capable to work ahead and achieve, without punishing anyone by setting all standards for all students too high, just the ones who take AP. Sound like a good idea on the surface, right?

If you start to deconstruct AP classes and tests you run into some pretty disturbing trends, motives, biases, inequities, and truths (or lack thereof).

It is pretty well documented that AP curricula were hyperfocused on content retention for many years. The newer models and redesigned classes are slightly more skill-focused, but those older classes running for decades as they were had lasting effects. Teachers trained for and worked in those systems for years, which can affect how the do things for their entire careers, and how students grow up to attempt to do, learn and even teach. The newer AP courses are still quite heavy in measuring content retention. When it comes down to it, AP tests measure how well you remember a subject and some of the ways you can apply the content from that subject. The tests mostly boil down to a test of remembering information that is instantly accessible outside of a regulated AP test.

AP test scores can get you college credit. If you start to look at who does well on AP tests you quickly find out it is the students with all of the access and privilege. The good schools, with the highest average family socioeconomic status have the higher test scores. This means that the kids who would most likely benefit the most from getting some cheap college credit are not necessarily the ones getting it.

Why do high school students need to be earning college credit? This takes us down into another deconstruction rabbit hole. To graduate college early? I guess that argument could make some sense, but I have yet to find studies showing that is the result of AP test success. To save money? That seems like another good argument, but if you look at that reason it exposes another deep issue with our systems. College is unaffordable. If the reason to try to earn college credit in high school is that college credit is really expensive, that does not seem like a solid foundation for an education system. It sheds light on a major issue with another system. Or is the main reason to skip the poorly designed intro college classes that are akin to torture for many? Because that seems like a bad thing to shape a high school experience around.

You can dive deeper into those college systems and you don't ever arrive at any sort of foundation or truth that sounds anything like we do this because it is best for student development. It’s either about saving money or aligning with another system with even bigger issues. You never encounter any foundation built on a premise of healthy growth of a learner or the development of important skills.

You can dive into grading systems if the big picture alien idea wasn't enough for you. I won't hash out the deconstruction details again. It has already been a topic of some

previous blog posts by me. The result you get when you boil down our grading systems is that we do it because it's easiest, or cheapest, someone can make more money from it that way, we believe remembering stuff is learning, or that's just how it has always been done. None of those are healthy foundations.

The questioning of what is wrong with teaching standalone subjects is a hard one to see the big picture on for many. Humans find is quite helpful to categorize things. Drawing boundaries can help us wrap our heads around big ideas. We have physics class, and everything in that class is physics. If it was mixed up evenly with math and art and writing then maybe it would not seem as much like physics and we would not have as easy a time seeing the big picture and patterns and major physics concepts. It turns out, without creative outlets, and writing, and taking time to truly make meaning of the math, physics is pretty impossible to learn for many students. The best physics teachers get the best results incorporating skills and ideas from outside of what one would probably label physics.

If we start to boil down the systems of running standalone subject classes, they tend to break down to the same base reasons that grading systems often have -- money, it's easier, because we have always done it that way, because another faulty system does it that way (college), and/or a belief that remembering stuff is learning. The foundations are never what they should be -- that it best serves the needs and interests of every learner.

Bandaids or something better?

We have all of these systems with policies in place that don't really make any sense, and instead of fixing the actual problems we try working within the systems and bandaids. We try to make our grading systems more fair by allowing for make-up assessments. We try to convince kids to go to bed earlier, like that works. AP teachers give summer homework, as if that is going to fix summer retention issues, ignoring the fact the retention as a goal is the issue.

If you don't get to design the systems, it might not seem like you don't have much control or freedom. I write a fair amount of stuff that people seem to agree with in principle, but I get a lot of responses like,

"Yeah, but what am I supposed to do about it? I have to work in this system we already have. . . "

or,

"Tell that to the politicians!"

or,

"Changing how I do things is too scary, and I don't think I could pull that off."

All of those responses make sense to me. I lived all of those responses at some point.

So what is there to do? How can a teacher or admin affect change?

Be the change. Dconstruct your systems and rebuild them on solid foundations. This tends to be a crazy soul-searching endeavor that takes a while and it is best to do with a colleague or two.

Start the conversations and keep them going. If our systems are not rooted in what is best for students and they even harm many students then we should be talking about that all the time. K-12 educators are the best candidates for crafting the solutions. It can also help to reach out to college and university educators. You will probably have the most luck with professors in college of education that train teachers and do research in education, but there are some progressive professors in all colleges and departments who actually care about improving education systems.

Write to your politicians and policy makers. Tell them what is wrong. Even better, give them a solution. People love it when you give them a solution. They might even give you credit or ask you to be part of crafting the design details an implementation of a new system.

Advocate for students. Tearing down old systems and building new systems based on actually supporting young learners is advocating for students, but people might not realize that's why you are doing it unless you tell them.

Educate yourself. Stay informed. Stay up to date. Know that the research says, know what the opposition says, know what everyone says. Know what our students say. Know what your gut tells you.

Most important, know why. Know why we do things the way we do, and if the reasons are not good ones that are student-centered, then figure out how to make them so they are.